This article is part of a series in which I evaluate 2022 rookie running backs solely on their ability to run the ball. The Breakout Finder installments can be found here. The three PlayerProfiler installments can be found here. If you happened to already catch those and don’t need a refresher on my methodology, feel free to skip to the player-focused analysis below.

The Player

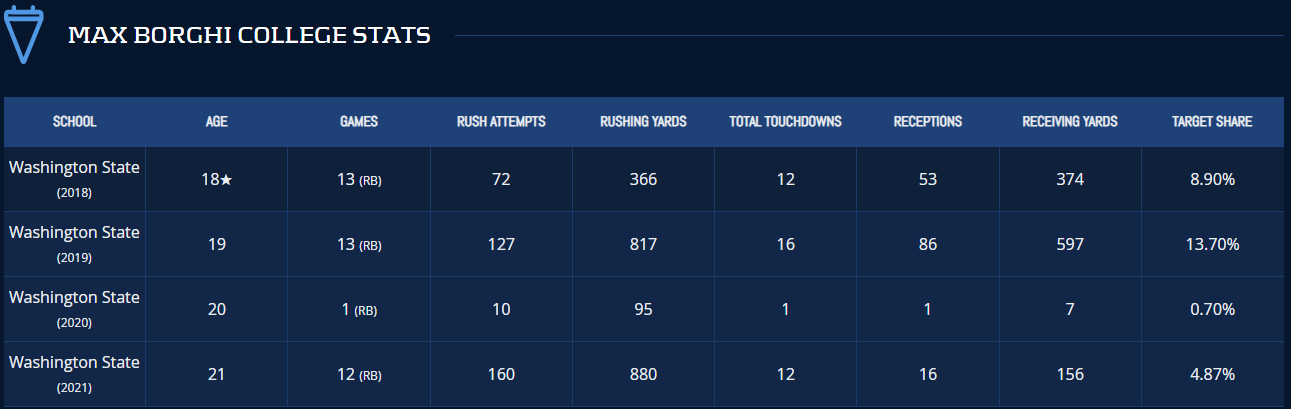

Washington State’s Max Borghi has been a name well-known in devy circles for a few years now. Given his pass-catching acumen (and, let’s be honest, his complexion), he was receiving hype as the next Christian McCaffrey early on in his college career. The people were a little out over their skis on that one. But general excitement about Borghi hasn’t been completely unwarranted. He broke out as a true freshman, is supposedly pretty athletic, and has been incredibly productive in the receiving game. He boasts an 85th-percentile Target Share and 98th-percentile per-game reception rate among running backs drafted since 2007. His receiving numbers tapered off a bit (ok, a lot) after Mike Leach (and the Air Raid offense) left the Cougars for Mississippi State in 2019. But there may still be reason for optimism about Borghi as an NFL prospect.

The Metrics

In four years in Pullman, really only three being that he missed all but one game of the 2020 season with a back injury, Max Borghi ran the ball 369 times while playing with backfield teammates who averaged a collective 2.89-star rating as high school recruits. That number makes them a 37th-percentile group. And Borghi was able to outdo them by 1.05 yards per carry over his career, a 75th-percentile YPC+ mark. He was also impressive from a big play-creation standpoint, He churned out chunk gains of 10+ yards at a rate 7.86-percent higher than the other Cougar backs. A performance ranking in the 94th-percentile.

Borghi was not as good in the open field. He turned those chunk gains into breakaways of 20+ yards at just a 23.2-percent clip, only a 17th-percentile mark. My completely untested hypothesis is that he might not actually be a bad open field runner. Rather, it’s simply more difficult to rip off huge gains while operating in an offense like the Air Raid; with the defense just waiting for you in the secondary as they’ve backed up to stop the pass. Who knows?

A prolific pass-catcher, Borghi saw lighter box counts than those his teammates were facing. And the 0.11 fewer defenders in his average box make for a discrepancy in the 25th-percentile. However, he outdid other WSU runners against every box count he faced, save for three total carries against eight and nine-man boxes. And his overall BAE Rating of 124.4-percent is a 76th-percentile figure. Nearly identical to the degrees at which guys like Breece Hall and Javonte Williams outperformed their teammates.

Rushing Efficiency Score and Comps

Using all of the non-BAE metrics that we’ve touched on here, in addition to overall team strength, offensive line play, rushing volume, and strength of opponent, my model’s composite Rushing Efficiency Score has Max Borghi as a 61.6 out of 100. According to a BAE-centric composite rating that I’m currently workshopping, he earns a 56.2 out of 100.

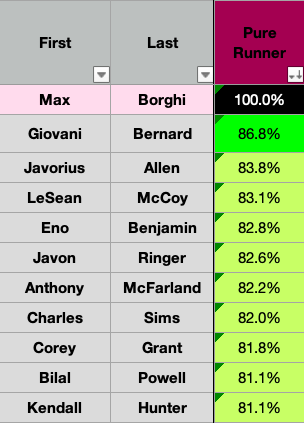

With the same inputs as the Rushing Efficiency composite, in addition to accounting for physical measurables, my model also generates comps for running back prospects from a “pure runner” perspective. Assuming he’s 206-pounds, just shy of 5-10, and runs a 4.45 40-yard dash, here are the most 10 most similar runners to Borghi:

Borghi is a difficult evaluation for a few reasons. First, he was a productive receiver, but his usage and efficiency as a pass-catcher were not overly impressive. He wasn’t often being split out wide or catching passes downfield. The possibility of his being a high-volume checkdown guy seems likely relative to the alternative of his being a legitimate Christian McCaffrey or Alvin Kamara-like weapon in the passing game. Second, the unique offensive environment that he operated in makes clean, one-to-one comparisons of his efficiency to backs from more traditional systems difficult. He saw easily the lightest average box count of any back I’ve collected box count data on so far. The 5.58 average box defenders he faced is almost a half-defender lighter than the second-lowest mark of 6.07 that classmate Keaontay Ingram ran against.

Last Word

I’m not really sure what to do with Max Borghi in this running back class. He’s a high-volume, low degree-of-difficulty receiver. And he was a runner who was awesome relative to mediocre teammates in a bizarre system. If his skills are translatable, he could end up somewhere on the Duke Johnson–Giovani Bernard spectrum; as a useful PPR asset with sneaky three-down ability. I think the more likely scenario is that he was the running back version of Graham Harrell; a productive player in a high-octane system who simply isn’t special at the professional level. I would defer to film analysts on how “for real” we should view Borghi as being. Given the lack of love I’ve seen from him in the prospecting realm, I can’t imagine many are particularly enthused.

From a valuation standpoint, Borghi’s chance to hit the high-end of his range of outcomes doesn’t seem that different than other pass-catching types in this class, like Tyler Badie or Jerrion Ealy. He’s got good size for a satellite back. If you’re looking to throw darts in deep leagues, you could do worse than a guy who was impressive as a producer, runner, and receiver in college.